The remarkable Mr.Ive

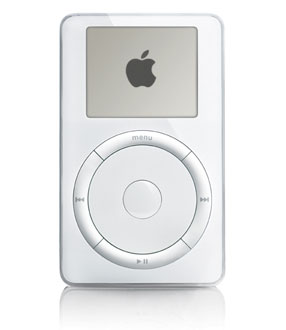

As the head of design at Apple, Jonathan Ive has combined what he describes as “fanatical care beyond the obvious stuff” with relentless experiments into new tools, materials and production processes, to design such ground-breaking products as the iMAC, iBook, the PowerBook G4 and the iPod MP3 player. He won the Design Museum's first Designer of the Year prize for the 2002 iMac and iPod.

Born in London in 1967, Ive studied art and design at Newcastle Polytechnic before co-founding Tangerine, a design consultancy where he developed everything from power tools to televisions. In 1992, one of his clients – Apple – offered him a job at its headquarters in Cupertino, California. Working closesly with Apple’s co-founder, Steve Jobs, Ive developed the iMac. As well as selling more than 2m units in its first year, the iMac transformed product design by introducing colour and light to the drab world of computing where, until its arrival, new products were encased in opaque grey or beige plastic.

Ive and his close-knit team of designers at Apple have since applied the same lateral thinking and passionate attention to detail to the development of equally innovative new products such as the Cube, the iPod and the PowerBook G4, the world’s lightest and slimmest 17 inch laptop, and the ultra-slim iMac G5.

Q. How did you you first become interested in design?

A. I remember always being intrested in made objects. The fact they had been designed was not obvious or even interesting to me initially. As a kid, I remember taking apart whatever I could get my hands on. Later, this developed into more of an interest in how they were made, how they worked, their form and material.

Q. When did you decide to pursue design as a career and how did you go about it?

A. By the age of thirteen or fourteen I was pretty certain that I wanted to draw and make stuff. I knew that I wanted to design but I had no idea what I’d design as I was interested in everything: cars, products, furniture, jewellery, boats. After visiting a few design consultancies I eventually decided that product design would be a pretty good foundation as it seemed the most general. I studied art and design at school and went on to Newcastle Polytechnic. I figured out some basic stuff - that form and colour defines your perception of the nature of an object, whether or not it is intended to. I learnt the fundamentals of how you make things and I started to understand the historical and cultural context of an object’s design. I wish my drawing skills had improved, but while that bothered me then, it doesn’t now.

Q. After graduating, you joined the design consultancy Tangerine. In retrospect, how useful was your experience there?

A. I was pretty naïve. I hadn’t been out of college for long but I learnt lots by designing a range of different objects: from hair combs and ceramics, to power tools and televisions. Importantly, I worked out what I was good at and what I was bad at. It became pretty clear what I wanted to do. I was really only interested in design. I was neither interested, nor good at building a business.

Q. Why did you decide to join Apple?

A. I went through college having a real problem with computers. I was convinced that I was technically inept, which was frustrating as I wanted to use computers to help me with various aspects of my design. Right at the end of my time at college I discovered the Mac. I remember being astounded at just how much better it was than anything else I had tried to use. I was struck by the care taken with the whole user experience. I had a sense of connection via the object with the designers. I started to learn more about the company, how it had been founded, its values and its structure. The more I learnt about this cheeky almost rebellious company the more it appealed to me, as it unapologetically pointed to an alternative in a complacent and creatively bankrupt industry. Apple stood for something and had a reason for being that wasn’t just about making momey.

Q. What are the advantages of designing for one company? And the disadvantages? What are the particular characteristics of the set-up at Apple that has made the experience of working there rewarding for you?

A. It is pretty humbling when so much of your effectiveness is defined by context. Not only is it critical that the leadership of a company clearly understands its products and the role of design, but that the development, marketing and sales teams are also equally committed to the same goals. More than ever I am aware that what we have achieved with design is massively reliant on the commitment of lots of different teams to solve the same problems and on their sharing the same goals. I like being part of something that is bigger than design. There is a loyalty that I have for Apple and a belief that this company has an impact beyond design which feels important. I also have a sense of being accountable as we really live, sometimes pretty painfully with the consequences of what we do.

Q. Similarly, what are the advantages - and disadvantages - of concentrating on the design of a particular product, in your case, the computer? And is the computer a richer and more rewarding area of design for you to concentrate on now than other products?

A. I had been concerned that moving away from working independently for a number of clients on a broad range of products would be difficult. Surprisingly this has not been an issue, as we are really designing systems that include so many different components - headphones, remote controls, a mouse, speakers as well as computers. The issue has really been the focus on designing technologically based products. I love working within such a relatively new product category. The opportunities are remarkable as you can be working on just one product that can instantly shatter an entire history of product types and implicated systems. The iPod is a good example as it is not only a very new product but it clearly turns our users’ previous experience and understanding of storing and listening to music upside down.

Q. What are the defining qualities of the design of an Apple product? To what degree are they related to the design heritage of Apple before your arrival there?

A. In the 1970s, Apple talked about being at the intersection of technology and the arts. I think that the product qualities are really consequent to the bigger goals that were established when the company was founded. The defining qualities are about use: ease and simplicity. Caring beyond the functional imperative, we also acknowledge that products have a significance way beyond traditional views of function.