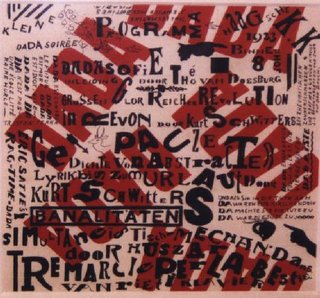

(consider David Carson's work in relation to Schwitter's)In the winter of 1918, Germany plunged into revolution; the Great War was ended and the Weimar Republic proclaimed. When the revolution reached the city of Hanover, Kurt Schwitters was working as a mechanical draftsman in an ironworks outside the city, while painting and writing poetry in his spare time. He was thirty-one, and beginning to make a small reputation for himself: that June, some of his paintings had been exhibited at the renowned Sturm gallery in Berlin. . . .

Schwitters (1887-1948) started his career as an expressionist painter before turning to wood constructions and paper collages in 1917. While being associated with not only the German Dada movement but also artists from the Bauhaus and de Stilj in Holland, Schwitters was always fiercely independent and avoided being absorbed into any of the avant-garde art movements that flourished in Europe between the wars.

Schwitters (1887-1948) started his career as an expressionist painter before turning to wood constructions and paper collages in 1917. While being associated with not only the German Dada movement but also artists from the Bauhaus and de Stilj in Holland, Schwitters was always fiercely independent and avoided being absorbed into any of the avant-garde art movements that flourished in Europe between the wars.Living in somewhat easy prosperity in Hanover, he was sometimes belittled by his Berlin Dada colleagues for his lack of enthusiasm with radical politics. Inventing the name "Merz" in 1920, he became, in effect, a one-man art movement, best known for his mastery of the art of collage and for his contribution to the history of radical typography through his various journals and other publications.

Included in Hitler's Entartete Kunst (degenerate art) exhibition, Schwitters, like many of his contemporaries, left Germany in 1937, initially moving to Norway and three years later, as the German army advanced, he fled again to Scotland only to be arrested and interned as a an enemy alien. By 1943, he was living with his son and daughter-in-law in London, scraping together an income from commissioned portrait paintings and continuing to work on his 'Merz' collages and constructions.

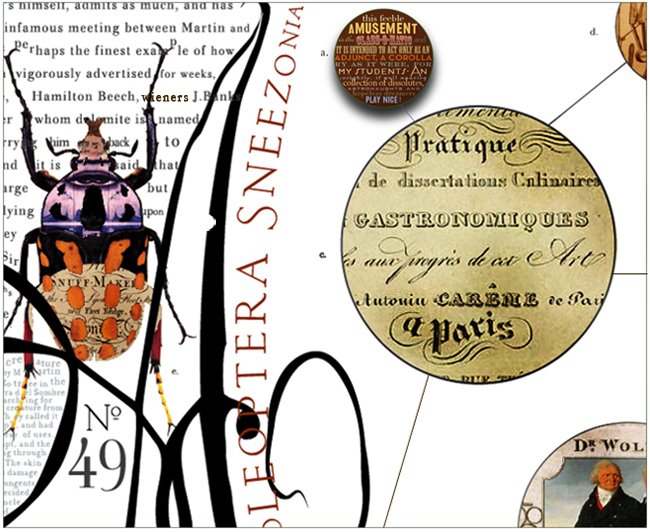

Created in war-ravaged London in 1943, the title Out of the Dark may be a reference to renewed optimism in the efforts of the allied forces or perhaps to the possibility of being able to work in daylight after the long nights of enforced blackout. Although collaged from an Australian fruit label, emphasis is given in the composition to the words "British Empire". Considering the artist's poverty and obvious alienation as a German citizen in London, it is also an ironic reference to the deprivation of the times; a box of fresh apples would have been an extreme luxury and the artist's lifestyle is hinted at through the bus ticket to the Fulham Road and the printed one penny coin (with Britannia turned decidedly on her head).

A subtle shift occurred in Schwitters' work, living as an exile, in relative isolation from his previous colleagues. In some of the English collages there is a more pronounced use of found imagery as the predominant element in the overall composition which inevitably suggests more 'meaning' to the work. The overall abstract composition is no longer more important than individual collaged elements. Another collage from the year before The Proposal 1942 (also known as The Courtship) uses as its base a 19th century lithographic illustration of a family sitting around a table that is almost puritan in its restraint on which is collaged reproductions from a glossy magazine of plates of food - biscuits, roast chicken, doughnuts, tarts etc. The culture of prosperity alluded to in this and other 1940's collages is very obviously America, as gleaned by Schwitters through American magazines sent to him by his friend Käte Steinitz who had emigrated there in 1936.

The shift in Schwitters' collages from an emphasis on composition to a subtle, yet unmistakable, social comment, is the most important development to emerge in the work of his late, 'in exile' period. While visually, this may appear to be a seemingly insignificant shift in emphasis, it has much in common with the early work of The Independent Group which, in turn, developed into Pop Art.

No comments:

Post a Comment