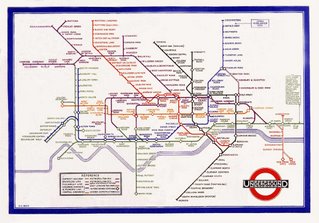

" The London Underground Map. What a piece of perfection it is,

created in 1931 by a forgotten hero named Harry Beck, an out-of-

work draughtsman who realized that when you are under ground

it doesn't matter where you are. Beck saw - and what an intuitive

stroke this was - that as long as the stations were presented in their

right sequence with their interchanges clearly delineated, he could

freely distort scale, indeed abandon it altogether. He gave his map

the orderly precision of an electrical wiring system, and in so doing

created an entirely new, imaginary London that has very little to

do with the disorderly geography of the city above. " excerpted from

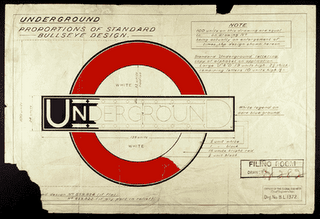

Notes from a Small Island - by Bill BrysonUnderground Roundel

The roundel, symbol of London's public transport and a powerful

icon of the city itself, is almost 100 years old. From its humble

beginnings as a platform name board in 1908, the roundel has

become a famous company trademark, providing a unified corporate

identity for all London's transport services. The famous roundel,

originally known as the bar and circle, was first introduced on station

platforms in 1908 in an attempt to make the station name more clearly

visible on walls cluttered with commercial advertising and billboards.

The early platform bar and circle was a solid red, vitreous enamel disc,

fitted with a horizontal blue and white name bar framed with timber

moulding. From about 1911, the Underground logotype, with its large

U and D and hyphens, began to appear across the bar of the bar and circle

symbol. However it was not until 1913, when publicity manager Frank Pick

commissioned the typographer Edward Johnston to design a company

typeface that the roundel began standardised.

He was then asked to apply his successful sans serif typeface to the bar and

circle in 1916. Johnston reworked the Underground logotype in his new

typeface and incorporated it with a red ring. Johnson's version of the roundel

was registered as a trademark in 1917. Thus the roundel finally arrived as one

of the first corporate identity symbols and although over the years has been

refined it still retains its essential origins.

and no, that's not my dad on the right...