Met Won’t Show a Grosz at Center of a Dispute

By ROBIN POGREBIN

Published: November 15, 2006

In response to an ownership dispute, the Metropolitan Museum of Art says it has decided not to borrow a painting by George Grosz from the Museum of Modern Art for an exhibition of German Expressionist portraits that opened yesterday.

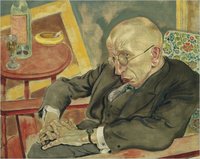

“The Poet Max Herrmann-Neisse” (1927), by George Grosz.

click to enlarge

The artist’s estate argues that it is the rightful owner of the 1927 portrait of the poet Max Hermann-Neise, & another work by Grosz in MoMA’s collection. MoMA, which has been discussing the issue with the estate for three years, counters that it has thoroughly investigated the claim and has concluded that it has no legal basis.

The artist’s estate argues that it is the rightful owner of the 1927 portrait of the poet Max Hermann-Neise, & another work by Grosz in MoMA’s collection. MoMA, which has been discussing the issue with the estate for three years, counters that it has thoroughly investigated the claim and has concluded that it has no legal basis.Rather than the 1927 painting, the Met is featuring a 1925 portrait that Grosz painted of Herrmann-Neisse, borrowed from the Städtische Kunsthalle in Mannheim, Germany, in the exhibition “Glitter and Doom: German Portraits From the 1920s,” which opened yesterday.

“We don’t want to be in the middle of any challenges or discussions,” said Harold Holzer, a spokesman for the Met. “It seemed more prudent to have the earlier version.” The Grosz estate has not taken legal action against MoMA, although the estate’s managing director, Ralph Jentsch, said in an interview that he was considering it.

“It’s our property,” said Mr. Jentsch, who says he was appointed to his post by Grosz’s two sons, Peter and Martin, in 1994. (The elder son, Peter, died in September at 80.) “It doesn’t belong to MoMA.” According to correspondence provided by the estate, it first advanced its claim to the two paintings in a letter to MoMA on Nov. 24, 2003. Mr. Jentsch argued that they were sold without the consent of the artist, who had consigned them to an art dealer, Alfred Flechtheim, in 1928-29.

Both Grosz and Flechtheim fled Germany in the face of Nazi persecution, the letter noted. (Grosz’s art and politics were viewed as unpalatable by the regime, and Mr. Flechtheim was Jewish.) The artist left a few weeks before the Nazis came to power in 1933, Mr. Jentsch wrote, “and Flechtheim fled to Paris when his gallery in Berlin was confiscated” afterward. Mr. Jentsch said that the Herrmann-Neisse portrait was confiscated by the Nazis in 1933 at the Flechtheim Gallery in Berlin and that it reappeared in 1952, when it was bought by the Modern for $850 from Charlotte Weidler, a German immigrant.

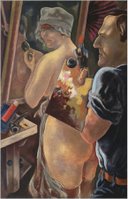

He says the other disputed painting, “Self-Portrait With a Model” from 1928, was sold for $10 in 1938 “at a deceitful auction” in Amsterdam to which it was consigned by Mr. Flechtheim.

MoMA acquired the self-portrait in 1954 as a gift from the children’s author and illustrator Leo Lionni, who had tried to auction it shortly before. (It did not meet its $110 reserve price, auction records show.) “As these Grosz works would not have been lost if Flechtheim and Grosz had not had to flee Germany in order to save their lives, the George Grosz Estate claims restitution,” Mr. Jentsch wrote.

But MoMA says that Ms. Weidler sold the Herrmann-Neisse portrait through a dealer who was a longtime friend of Grosz and that the artist was aware that the Modern had acquired it. The museum says Alfred Barr, MoMA’s founding director and a friend of Grosz’s, even invited the artist to sign the canvas.

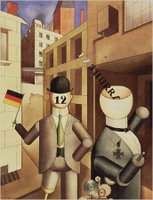

“Republican Automatons,” a 1920 watercolor by Grosz at MoMA; the work’s provenance is still being researched by the artist’s estate.

It also questions why Grosz, who died in 1959, failed to ask that the Herrmann-Neisse portrait be returned when he saw it at the museum. But Mr. Jentsch said, “What was he supposed to do, walk in there and say, ‘That’s my painting’?” Mr. Jentsch also quoted from a letter in German that he said Grosz wrote to his brother-in-law in 1953: “The Modern Museum exhibited a stolen painting of mine. (I am powerless.) They bought it from someone who has stolen it.”

It also questions why Grosz, who died in 1959, failed to ask that the Herrmann-Neisse portrait be returned when he saw it at the museum. But Mr. Jentsch said, “What was he supposed to do, walk in there and say, ‘That’s my painting’?” Mr. Jentsch also quoted from a letter in German that he said Grosz wrote to his brother-in-law in 1953: “The Modern Museum exhibited a stolen painting of mine. (I am powerless.) They bought it from someone who has stolen it.”Although Mr. Jentsch originally sought the restitution of a third work by Grosz, the 1920 watercolor “Republikanische Automaten” (or “Republican Automatons”), he said he later determined that the provenance of the 1920 watercolor required more research.

In MoMA’s first response to the estate, dated Dec. 4, 2003, Glenn D. Lowry, the museum’s director, wrote: “I take the matters you raise very seriously, and I have directed my staff to treat this as a matter of the highest priority.” At one point Mr. Lowry suggested to Mr. Jentsch that the museum and the estate share ownership of the paintings for a period of 5 or 10 years, while ownership was in dispute. If no determination were ultimately made, he suggested, the two could share custody in perpetuity.

“Before we remove a work from the museum’s collection,” Mr. Lowry said in a July 2005 letter to Mr. Jentsch, “we need to establish convincing and conclusive evidence that another party — in this instance the estate of George Grosz — has ownership rights superior to the museum’s.”

In January 2006, as discussions seemed to be approaching an impasse, MoMA asked Nicholas deB. Katzenbach, a former attorney general and undersecretary of state in the Johnson administration, to conduct an independent investigation to assess the claim. Three months later Mr. Katzenbach recommended that MoMA reject the claim.

“There is nothing in the record — nor does Mr. Jentsch indicate any facts — suggesting any bad faith, negligence or questionable conduct at any time by anyone connected with MoMA,” his report said. Mr. Katzenbach noted that when Grosz saw the Herrmann-Neisse portrait at the museum, he did not ask that it be returned or that he be compensated. Had he done so, the report added, “not only would the museum have had the opportunity to ascertain the facts when they were still reasonably fresh and knowable, but it would have had the opportunity to resolve the matter then and there at relatively little cost to it.”

This is not the first time Grosz works have been the subject of controversy. The Grosz estate filed a lawsuit in 1995 against the Manhattan art dealer Serge Sabarsky, arguing that Mr. Sabarsky had deprived the estate of appropriate compensation for the sale of hundreds of Grosz works he had acquired. The lawsuit was settled last summer.

Although Mr. Jentsch agreed to cooperate with Mr. Katzenbach’s inquiry, he rejects his conclusion, partly because, he says, Mr. Katzenbach failed to translate some of the German documents Mr. Jentsch had given him Mr. Jentsch said he was meeting with lawyers and would decide by the end of the month whether to file a court challenge. If his bid to recover the paintings were to succeed, he added, he would display them in a new Grosz museum he hopes to found and direct.

If the portrait of Herrmann-Neisse were put up for auction today, it would probably fetch about $2 million, market experts say. But Mr. Jentsch said, “We’re not interested in making money.”

George Grosz’s “Self-Portrait With a Model” (1928),

George Grosz’s “Self-Portrait With a Model” (1928),one of two works at MoMA to which the artist’s estate

has laid claim for several years.

No comments:

Post a Comment